Dynamo Dresden and the two Germanys

Why are chants still being sung in the stands of Dynamo Dresden that refer to East Germany?

Dresden.

April 19, 1989.

The second leg of the UEFA Cup semi-final had just ended. Dynamo Dresden faced Stuttgart. In the first leg, Stuttgart won 1-0. The yellow and blacks were unable to overturn the result. At the final whistle, the scoreboard read 1-1.

A draw that allowed Stuttgart to reach the final, where they would meet Maradona's Napoli and lose. That semi-final of the UEFA Cup represents the highest point in the history of Dynamo Dresden. From that moment, a catastrophic decline began for one of the best teams in the GDR.

A few months later, the wall would fall, marking the end of the German Democratic Republic. Germany would become one.

Yet, more than 30 years later, the fans in the stands of Dynamo Dresden still sing a chant that goes:

“Ost, Ost, Ost Deutschland”.

Which means “East, East, East Germany”.

But why do they still refer to East Germany today if it no longer exists?

What does the history of Dynamo Dresden teach us about the reunification of Germany?

And how politicized is German football?

The German peoples

Germany is a much more complex country than many imagine. And I am not referring to the difficulty of the language—rather, its history and especially its ethnic composition.

Have you ever noticed that Germany is called differently depending on the language in which it is pronounced?

In English, it is Germany.

For the French, it is Allemagne.

For the Spanish, it is Alemania.

In Polish, it is Niemcy.

In Serbian, it is Njemacka.

For the Finns it is Saska.

The concept of Germany as a single nation-state only arose in 1871 with the reunification of Otto von Bismarck. Unlike England or France, Germany was not created by the expansion of a conquering centre but by the voluntary union of several Germanic peoples.

The territory that now corresponds to Germany was inhabited by several tribes. In German, it is Stämme. Swabians, Bavarians, Saxons and Franconians. In the first centuries of German history, the tribes were the most important political units within Germany. After the dissolution of the tribal duchies into numerous smaller principalities, the tribes remained as cultural and linguistic units, expressed in their dialects and their folk culture.

Even today, the awareness of tribal belonging varies from region to region. This is probably most pronounced among the Bavarians. In eastern Germany, the formation of the new federal states led to a revival of tribal consciousness. This allows us to understand something very important: There has never been a German volk.

It is false to speak of a German nation.

Thomas Mann

Returning to the different ways in which Germany is called from the outside, this happens because each foreign people had given it a name based on the tribe that lived closest to them, or a characteristic of that specific tribe.

The Alemanni represented a large group of various tribes that lived in the areas that today go from the border with Switzerland to the Rhine River. The French renamed them as "all men", which then became "Allemagne".

For the Slavs who bordered the German tribes, these people were “nemets”. A word from Proto-Slavic, which can be translated as "difficult to understand" or "the silent ones".

The name of the Saxons, which refers to the tribes that lived near the North Sea, derives from the proto-German “sakhsan”, which was most likely a type of knife. Consequently, Germany is called Saksamaa by the Estonians and Saska by the Finns.

Since the day of Otto von Bismarck's reunification, Germany would have been an important protagonist in History. With two lost world wars, the internal division and then the fall of the Berlin Wall. The event that marked the end of the Cold War, communism and the Soviet Union.

A year later, Germany reunited, becoming one.

But did it succeed?

The two Germanys

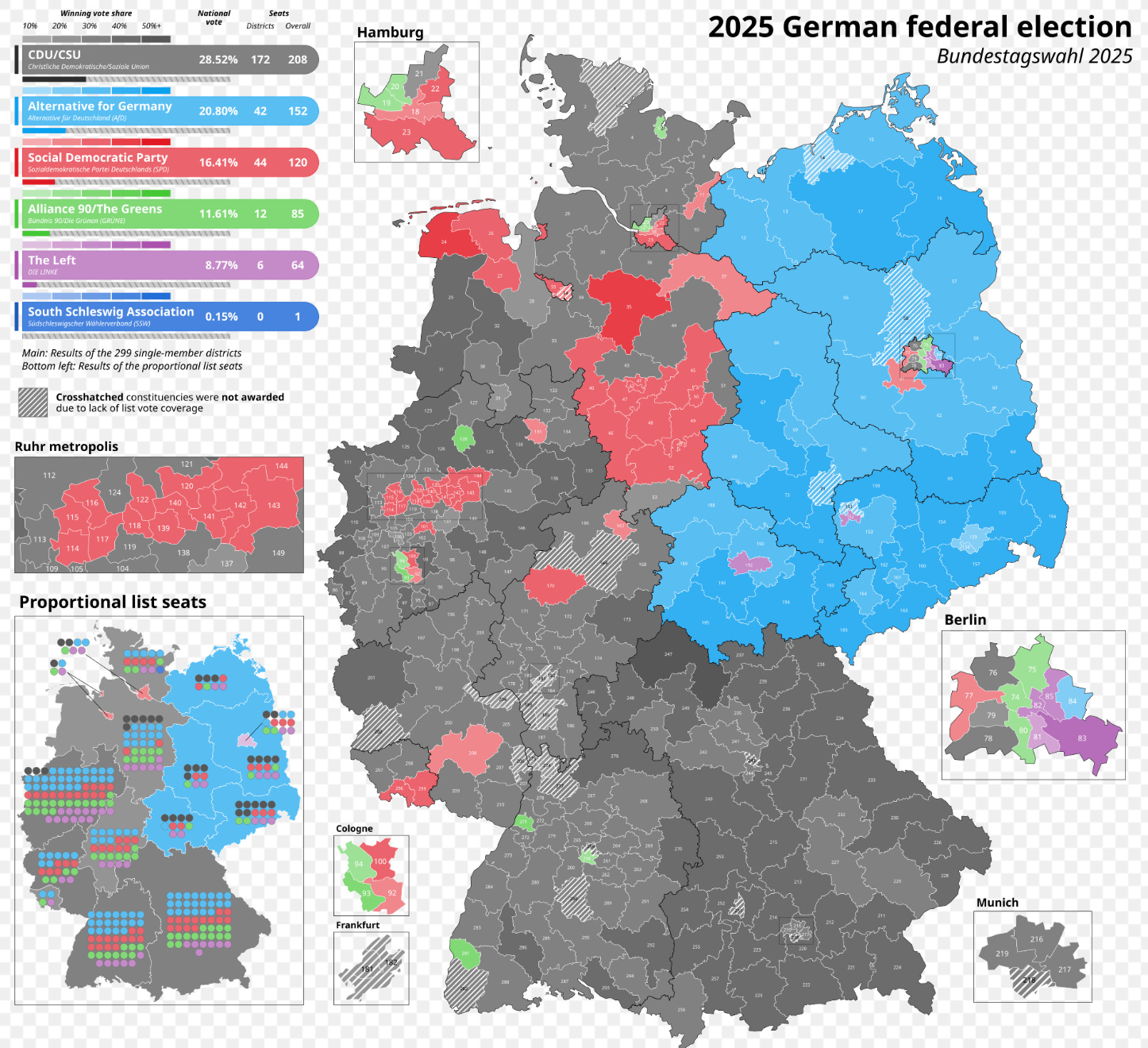

The image of the last elections is enough to understand that 35 years after unification, Germany is still divided.

This image is from 2025 and shows the result of the elections held in Germany last February 23. The division is evident to everyone. The borders are the same as they were before the fall of the wall. The bricks are no longer there, but in the vast majority of the former GDR, the AfD won.

I love Germany so much that I prefer two of them.

Giulio Andreotti

Der Spiegel, on the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the wall, titled “Ziemlich beste Deutsche”. Playing on the German title of the film “Intouchables”, making it “almost better Germans”.

And it wondered why the Germans were struggling to become a folk. Because they are not and never will be. Reunification took place from a legal point of view, but in reality, the division has never disappeared.

The East, in all these years, has remained the poorest part of the country. Former GDR citizens still earn lower salaries. In top positions, both in companies and universities, there are people from the West. The only exception to the rule was Angela Merkel.

Several geopolitical analysts describe reunification more as an annexation by West Germany. In fact, it was the former GDR that became part of the capitalist system and had to change its economy, culture and social rules from one day to the next. It is a process that would take several years, but West Germany thought it could be done quickly.

A process in which the former West Germany adopted an attitude of superiority. Jan Plamper describes it in his book “Das neue wir” when he analyses racism in the former GDR. He explains how an indirect cause of that phenomenon was also the arrogance of the West Germans, who described the East Germans as “bad and racist” and declared that racism in Germany came mainly from the East. This gave rise to a simplistic thought that anything negative that happened in Germany came from the East.

An arrogance that was especially evident in football. After the fall of the wall and the birth of a single State, there was a need to unite the two football leagues. And in the methodology that was adopted, there is the whole superiority complex of the West Germans.

The Killing of DDR Football

GDR football was not a low-level football; on the contrary. Magdeburg won the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup in 1974. Carl Zeiss Jena and Lokomotive Leipzig both reached the final. Dynamo Dresden reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Cup. These are results and milestones that need to be mentioned before we look at how football reunification came about.

The East German Oberliga was integrated into the Bundesliga using a pyramid scheme. The top two teams in the league were added to the Bundesliga. The third to sixth teams ended up in the Zweite Bundesliga or second division. The seventh to twelfth teams had to play playoffs to get into the second division.

This choice immediately shows a low consideration for East German football. This decision was the cause of the decline of the teams from the East. From that point on, there have never been more than two teams from the former GDR in the Bundesliga. Excluding RB Leipzig, which was founded in 2009.

The teams that paid the price were those that had written the history of GDR football:

Hansa Rostock

Magdeburg

BFC Dynamo

Carl Zeiss Jena

Lokomotiv Leipzig

Energie Cottbus

Dynamo Dresden

Dynamo Dresden

The city of Dresden, after being completely destroyed in World War II, became part of the GDR and played an important role in sports. The regime wanted to have representative clubs for cities such as Berlin, Dresden and Leipzig.

Dynamo Dresden had a predecessor: SV Deutsche Volkspolizei Dresden. A club that was moved to Berlin to create BFC Dynamo. Better known as the favorite club of the Stati, the East German secret service. Dynamo Dresden was officially founded in 1953.

The first years were very complicated. There was an immediate descent to the fourth division in 1957, followed by a slow climb back to the first division. The team only began to shine in the 1970s. Winning their first title in 1971, repeating in 1973, and then winning three in a row from 1976 to 1978. They were the first team to win the national championship and cup. Outside the borders, their greatest achievement was reaching the semi-finals of the UEFA Cup in 1978.

They were one of the most important clubs in the GDR, and their last team featured future champions such as Matthias Sammer and Ulf Kirsten.

With the reunification of German football, Dynamo Dresden was included in the Bundesliga.

And from that moment, a slow and inexorable decline began.

Photo: Philipp Rostig

The decline on the pitch

One factor that influenced the decline of Eastern teams in general was the economic attraction of the West. Now that players could move, many of them decided to go and play for other Bundesliga teams or in other countries. And Dynamo Dresden was one of the clubs most affected in this sense. They lost important players such as Ulf Kirsten, who moved to Bayer Leverkusen, and Uwe Rösler, who signed for Manchester City.

Dynamo's survival in the Bundesliga lasted four seasons. All spent fighting to avoid relegation. Relegation, however, came in 1995, with a last place and nine points away from the safety zone. A disappointment, a tragedy for a club like Dynamo. But that was only the first step in a very long descent into hell.

In the meantime, the club had gone into debt and had a total debt of around 10 million francs. Financial situation that prevented them from receiving the license to register for the Zweite Bundesliga. And so they were forced to a further relegation, to the third division. A nightmare.

But it was not over yet, because in 2000 the reform of the third German division reduced the championships from four to two. Dynamo Dresden failed to finish the season in the top seven places and was forced to relegate to the fourth division. Waiting for them were their rivals from the golden age: Magdeburg and BFC Dynamo.

In all these years, the slow and inexorable decline was not the only reason why Dynamo made headlines. Every time the yellow and blacks ended up in the pages of the newspapers, it was for something that had happened off the pitch. Usually for the deeds of their fans.

The explosion off the pitch and the ties to the far right

Unlike English football, where tribalism tends to revolve around inter-city or regional rivalries, the German game has long been tied to politics.

Simon Hughes

German football is highly politicised. One of the reasons for this strong link between football and politics is closely linked to the 50+1 rule. The associative model present in German clubs allows fans to have a lot of freedom of expression and to have a role in deciding what their clubs should represent.

The most famous and iconic case of German football is St. Pauli. The team from Hamburg is famous for being openly left-wing and for fighting important battles. There are also cases of clubs with supporters close to right-wing politics. Such as Borussia Dortmund, FC Chemnitz and even Dynamo Dresden.

Such closeness, in normal times, would not be a cause for concern. But recent times in Germany have been anything but normal. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Olaf Sholz had declared the Zeitenwende, with a fund of 100 billion euros untied from the debt brake rule. Which had as its objective to strengthen the German army. Zeitenwende that remained only on paper. Easier to bypass a constitutional law, rather than change the culture of a people.

Then, the collapse of the government composed of SPD, FDP, and Grüne caused early elections. A shock in a country used to having the same chancellor for 16 years in a row. And before the elections, for the first time since the Second World War, a motion was approved thanks to the votes of the AfD. This decision brought down the so-called Brandmauer, or the ideological wall erected by the German parties to prevent the return of the far right in Germany. A wall that included the agreement to never collaborate with the far right.

And finally, in the February 23 elections, the AfD achieved its best result since its foundation. Germany is in one of the most difficult moments in its recent history.

Back at Dynamo Dresden, the decline in performance on the field was accompanied by an explosion of support in the stands. A process that had both positive and negative effects.

Over the past 13 years, the club has found itself paying an average of 100 thousand euros in fines per season due to the actions of its fans. They were the protagonists of several acts of violence in the stands and gestures prohibited by the German Football Federation, including chants or gestures referring to the Nazi era.

But to understand the origin of this violence and, above all, the closeness of the yellow-and-black fans to the far right, it is necessary to take a step back and go to 1991. The year in which the team was banned by UEFA because some fans threw stones on the pitch and sang racist chants.

Those were the years in which the presence of far-right supporters became increasingly present in the stadium. It was normal to hear chants praising Nazism, songs against Jews or animalistic noises towards black players.

Chants like this were sung: “We will build a metro from Jerusalem to Auschwitz”.

Among the most extremist fringes of the yellow-black fans, there is the ultras group “Faus des Ostens”, accused of having created a criminal organization. An openly neo-Nazi hooligan group, founded on April 20, 2010. Adolf Hitler’s birthday.

Over the years, the group has been the protagonist of acts of violence, for the use of Nazi slogans and various clashes both with opposing fans and with the German police. Over time, the group has been prevented from entering the stadium.

Many football fans will have asked themselves: ‘AfD is starting its football club? I thought Dynamo Dresden already existed’

Grinsen von Böhmermann

Over the years, Dynamo Dresden fans have earned a reputation as one of the most passionate fan bases in German football. In addition to fines for violent acts, they have always recorded an average attendance of 25,000 at home games. A significant number, considering that the team plays in the third division.

What has caused a stir is how a team that was born with Soviet tendencies has moved closer to the far right. Normalizing things like pro-Nazi banners and chants and repeated violence makes the yellow-and-black ultras among the most feared in all of Germany.

It is necessary to underline that the fines that the club has received due to the behaviour of some of its fans very rarely had anything to do with political motives. Most of the time, they were imposed for property damage, disturbance of public order or acts of violence. The last fine received for political reasons occurred in 2018 when a fan made the Roman salute.

Of course, like any situation, this one is also complex. We must not make the mistake of considering the city of Dresden, but especially the club, as a far-right reality. If certain ultras sympathize with certain political ideologies, many other fans have different ideas. The yellow and black fans are not a monolith, far from it.

What does not help in this sense is still the superiority complex that exists in West Germany when talking about a phenomenon that occurs in the East. It is not uncommon to hear comments such as "typical of Dresden" and "typical of East Germany". An attitude that blames the East for everything bad that happens in Germany and shows us how the division has never disappeared. On the contrary, it has probably only increased.

The Far Right in East Germany

At first glance, the rise of the AfD in East Germany makes no logical sense. A far-right party, in what was a communist state. A party that pursues policies such as stricter controls on migrants and their remigration, in a territory that has the lowest percentage of migrants in all of Germany. According to this logic, the AfD should not be able to obtain so many votes.

The rise of the far right in East Germany is much more than all this. To understand this phenomenon, one must analyze the complexity of German reunification. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, a radical economic and social transformation began for the Länder that made up the former GDR. Driven by the desire and the rules imposed by West Germany.

The first consequence was the collapse of local industry, which caused an avalanche of layoffs. After 40 years of secure employment, people found themselves unemployed for the first time in their lives and without prospects for the future. To make this shock even worse, they saw their social status deteriorate, just as they had become part of that world that was theoretically better than theirs. They had expected anything except to become unemployed, poor and without a future.

The birth of feelings such as frustration and distrust towards the federal state was the first effect of all. Distrust only increased due to how the unification was managed. For many citizens of the East, it was simply a unilateral annexation by the West.

The Treuhandanstalt government agency decided to sell off state-owned companies and completely privatize the economy of the former GDR. The introduction of the German mark was announced, and no one bothered to think that workers from the East would need gradual integration. The East was reduced to a place where cheap labor could be found.

All this created a deep sense of alienation and non-belonging in the citizens of the East, compared to the West. Social differences were also fundamental. The dictatorial past had left a deep mark on the population of the East. Accustomed to having an authoritarian education, militaristic propaganda and little exposure to diversity. These factors contributed to rooting a closed mentality and distrust of change.

Thus, the East became a breeding ground for the extreme right: neo-Nazi groups found a large following among disillusioned young people, often children and grandchildren of those who, in the post-unification period, had lost everything.

The rise of the AfD in East Germany goes far beyond issues such as immigration or the war in Ukraine. It is primarily a vote based on resentment towards the West and non-acceptance of the terms of reunification.

35 years later, differences persist. On all levels: economic, social and political.

The East, despite the billions invested by the State and the EU in its development, continues to perceive itself as a marginalized territory. The fear of further social and economic transformations, after decades of insecurity, fuels resistance to change and pushes a part of the population to support movements that promise stability and a symbolic revenge on the West.

This is also why, during Dynamo Dresden matches, fans still chant “Ost, Ost, Ost Deutschland”.

It is a cry of pain to remember that they have not felt part of what should have been a united State for 35 years. They feel like they belong to something else.

To an entity that no longer exists legally, but for them has never ceased to exist.

Sources:

https://www.vavel.com/en/international-football/2024/03/13/germany-bundesliga/1175945-debt-demotions-and-despair-the-downfall-of-dynamo-dresden.html

https://www.dw.com/en/german-reunification-what-happened-to-east-germanys-top-football-clubs/a-55134253

https://www.dw.com/en/dynamo-dresden-and-the-soko-dynamo-58-affected-but-they-mean-all-of-us/a-51033143

https://www.bundesliga.com/en/bundesliga/news/dynamo-dresden-club-by-club-historical-guide-24217

https://www.sportstrade.io/blog-detail/203/dynamo-dresden-the-team-where-the-far-right-rules.html

https://equaliserblog.wordpress.com/2010/11/08/dynamo-dresden/

https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/685054/45dd7efdbfb91c834e1e54240ceacf32/20200304-Stellungnahme-Dynamo-Dresden.pdf

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Faust_des_Ostens

https://www.spiegel.de/sport/fussball/dynamo-dresden-wie-man-das-problem-mit-rechten-fans-in-den-griff-kriegt-a-1258156.html

https://www.zeit.de/sport/2015-03/dynamo-dresden-fans-bvb/seite-2

https://www.welt.de/sport/fussball/article199539172/Juristische-Schritte-Sexistische-Banner-und-SS-Totenkopf-Dynamo-entschuldigt-sich.html

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/sport/dynamo-dresden-eine-liebe-in-sachsen-3917890.html

https://fussballknecht.de/probleme-mit-rechten-fans-hat-dynamo-dresden-ein-nazi-problem/

https://www.reddit.com/r/Bundesliga/comments/1io3nb9/dynamo_geht_gegen_die_partei_vor_gericht_per_post/?show=original

https://www.linkiesta.it/2022/09/ultras-dinamo-fascisti-calcio-destra-europa/

https://www.osservatorioantisemitismo.it/articoli/neonazismo-ed-estremismo-tra-i-tifosi-ultra-di-calcio/

https://www.tag24.de/nachrichten/neo-magazin-royale-jan-boehmermann-dynamo-dresden-afd-fc-bundestag-bashing-fussball-438526

https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5299823/2024/03/07/german-football-far-right-politics/

https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/09/05/eastern-germany-saxony-thuringia-elections-far-right-afd-cdu-bsw/

That's a great article.

The counterpart to this I guess is the BSG Chemie Leipzig to RB Leipzig story.

There's a red pill / blue pill sense in the RB vs Dynamo choice that encapsulates something of the wider dilemma facing the former East.

Really interesting article, where I only started reading from a football perspective !