Peter O'Connor: the first man to raise an Irish flag at Olympic Games

The Irish athlete who defied the British Empire

Peter O’Connor’s story is far more than a tale of athletic triumph. It’s a powerful narrative of love and loyalty to one's roots, unyielding courage in defending heritage, and challenging an empire against the odds.

The Birth of a Champion

Peter O’Connor was born on October 24, 1872, in Millon, England, the third of eleven children. His parents, originally from Wicklow, had briefly lived in England before returning to their beloved homeland. This connection to Ireland was a cornerstone of Peter’s life, a bond so strong that it would immortalize him in the annals of Irish history.

Peter grew up with two great passions: Irish nationalism and sports. He joined the Gaelic Athletic Association at a young age, but his athletic career began almost by chance. In 1894, during the annual Fleadh in Cleaggan, he competed in a jumping event—barefoot, no less—against opponents wearing spiked shoes. That day, he won all three jumping events, and from that moment, both the media and the public took notice.

From then on, athletics became his life. He competed across Ireland and in England, winning on what many considered enemy soil. The Meath Chronicle famously wrote that he “whacked the Saxons on their own ground.”

In 1901, in Dublin, Peter jumped 7.61 meters, setting a new world record. American journalists dubbed him the “Irish Antelope.” This record stood unbeaten for 20 years and remained the Irish record for an astounding 89 years.

A Missed Olympic Dream

If 1901 was the pinnacle of Peter O’Connor’s athletic career, the previous year was equally significant, though for different reasons. In 1900, the Olympics were held in Paris. Peter was in his peak form, and participating in the Games seemed a natural progression in his career. But Peter made a bold decision—he refused to attend. The reason was simple: if he competed, he would have to represent the United Kingdom, which he did not want to do.

Four years later, at the 1904 St. Louis Olympics, he again chose not to compete, this time due to personal difficulties in his marriage.

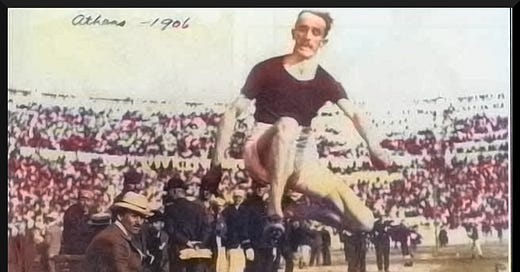

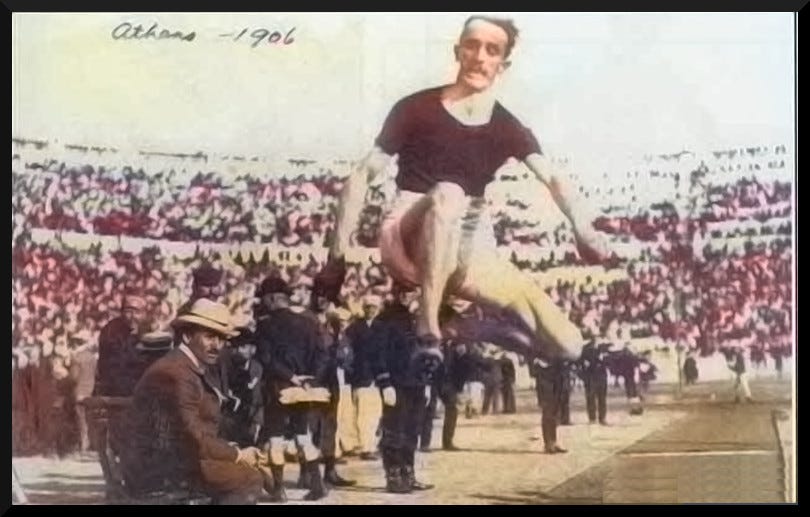

In 1906, the Intercalated Games took place in Athens, also known as the Second International Olympic Games by the Olympic Committee. It was here that Peter O’Connor would etch his name into the history of the Olympics and his country.

The Irish Flag

On April 12, 1906, Peter O’Connor, along with two other Irish athletes, Con Leahy and John Daly, arrived in Athens. The trio left Ireland convinced they were representing their homeland. But upon arrival in the Greek capital, they discovered they were listed as British athletes, representing the United Kingdom. Despite their protests and requests to compete under the Irish banner, they were told this was impossible since Ireland was not an independent state but a British colony.

O’Connor decided to compete regardless. He won the gold medal in what is now known as the triple jump. He should have also won the long jump, but with the only judge being the manager of the American team, the victory was unfairly awarded to his athlete.

Despite his achievements, the experience was tainted for O’Connor. But rather than letting it diminish his spirit, he chose to take a stand. During the medal ceremony for the long jump, as he stepped up to receive his silver medal, O’Connor made history. Everyone expected him to accept the medal under the Union Jack, but instead, O’Connor unfurled an Irish flag with the words “Erin go Brath,” meaning “Ireland till doomsday.” It was undoubtedly the first protest of this kind in the history of the modern Olympics.

O'Connor's act of defiance was set against the backdrop of the complex and often turbulent relationship between Ireland and the United Kingdom. At the time, Ireland was yearning for independence, and many Irish athletes, including O'Connor, used their platforms to express their desire for national recognition. His gesture at the 1906 Games was more than just a sporting moment; it was a poignant symbol in the broader narrative of Ireland's struggle for self-determination.

Irish is Not British

Today, the island of Ireland is divided into two states: the Republic of Ireland, an independent country, and Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom. The Republic of Ireland gained its independence in 1922, sixteen years after O’Connor’s bold stand in Athens.

Cillian Murphy explains that Irish is not British

British control over the island began in the 13th century. For centuries, the Irish people endured colonization. The island has always been home to the Irish, divided between Catholics and Protestants—the former predominantly in the south and northwest, the latter in the northeast. The landscape began to change in 1919 when the Sinn Féin party declared the birth of an Irish Republic. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919 - 1921). Following the war, the Catholics established the Republic of Ireland, while the 6 counties of Northern Ireland, mostly inhabited by protestants, remained within the UK.

In 1937, the new Irish constitution officially named the nation Éire, and in 1949, the Republic of Ireland left the British Commonwealth.

Yet, the Irish question was far from resolved. In the six counties that compose Northern Ireland, Protestants and Catholics have been living in uneasy coexistence. This tension gave rise to a conflict that would last for years, known as “The Troubles,” a violent struggle that claimed many lives. It wasn’t until 1998, with the Good Friday Agreement, that the violence stopped.

Brexit reignited old tensions. The United Kingdom's departure from the European Union raised the spectre of a physical border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. Aware of the potential consequences, British politicians worked to avoid reestablishing a physical border between the two states. The solution was to leave the border open between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, but to place one in the waters separating Northern Ireland from Great Britain.

Once again, sport serves as a lens through which we can better understand the world around us, the people who inhabit it, and the complex relationships between nations. More than a century after O’Connor’s protest, the Irish question remains unresolved. Since the UK left the European Union, two significant challenges loom for the British government: potential independence referendums in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland could push for unification with the Republic of Ireland. For this to happen, a referendum would need to be held in both Dublin and Belfast. According to the Friday Agreement, one key factor that might prompt such a vote is if Catholics become the majority. The data shows that since 2001, Catholics have gradually overtaken Protestants.

Source: nisra.gov.uk/Census2021

On February 3, 2024, power-sharing in Northern Ireland was restored, and Michelle O’Neill of Sinn Féin was appointed First Minister, marking the first time a nationalist politician has held this position. This has fuelled further debate about Northern Ireland’s future and the possibility of a referendum on Irish reunification within this decade. Michelle O’Neill declared that a border poll will happen before the decade is out.

Sources:

https://www.rte.ie/archives/2021/0721/1236415-unsung-hero-peter-oconnor/

https://irishsliceofmadrid.wordpress.com/2020/01/25/peter-oconnors-silver-medal-forgotten-olympian/

https://www.britannica.com/story/why-is-ireland-two-countries

https://www.irishfamilydetective.ie/post/2018/08/04/the-long-jumper-erin-go-bragh

https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/irish-reunification

https://www.politico.eu/article/joe-biden-northern-ireland-brits-screw-around/