Alisson Becker and German Emigration to Brazil

The second-largest group of Germans outside the country's borders is in Brazil.

July 8, 2014. At the Mineirao Stadium in Belo Horizonte, the first of two World Cup semifinals is over.

The scoreboard shows one of the most absurd results in the history of football.

Brazil 1 - 7 Germany.

For Brazilians, this defeat represents a collective trauma. It comes after only the most famous national football mourning: the Maracanãzo. The defeat in the World Cup final played at home in 1950 against Uruguay.

The drubbing against the Germans is renamed Mineirazo. Giving a name to the pain is the first step in grieving.

But if the whole country mourns, there is only one place in Brazil where Germany's victory may have pleased Brazilians. This is because the majority of the inhabitants have German ancestors.

It is in the state of Santa Catarina.

Santa Catarina

Santa Catarina is a state in which the vast majority of the population is descended from European settlers. The largest ethnic group is German, and roughly 45 per cent of the population still speaks Goethe's idiom.

One case that stands out is that of the town of Blumenau. Founded in 1850 in the middle of the jungle by German pharmacist Hermann Blumenau. One of the world's biggest Oktoberfests takes place here, after the one in Munich.

It is one of the 7 richest states in Brazil and with the best social indicators in all of Latin America. It is the second-largest state in terms of literacy rate and the fourth-largest in terms of income. Furthermore, it is thought that German emigration may have influenced this.

The state's cities are considered among the most liveable in the country and enjoy a reputation for being “clean, safe and organized.” In short, it is like being in a German enclave.

In the census conducted in 2000, about 12 million people in Brazil claimed to have German ancestry. Brazil is the second-largest group of Germans outside its borders. The first is in the United States.

But why did so many Germans move to Brazil?

German emigration

We have to take a huge leap into the past, back to the middle of the 19th century. At that time, there was no Germany as we know it today. Much of today's territory was part of the German Confederation.

In the early 1820s, poverty was quite widespread. There were several causes: consequences of the Napoleonic wars, fiscal oppression, and crop failures. Many of what we now call Germans were living in very difficult economic conditions.

Unexpectedly, there came an offer from Brazil, which only two years earlier had ceased to be a Portuguese colony. The offer consisted of land, livestock, seeds, farm equipment and financial assistance for the first two years to anyone who would be willing to move to the other side of the ocean.

Thus, in January 1824, on a ship called the Argus, 280 Germans reached Brazil. They settled in the states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande. Later, they founded the city of São Leopoldo, the first German settlement centre, in southern Brazil. The name was chosen to celebrate the Brazilian emperor's wife, Leopoldina. She had been in charge of the campaign to recruit the Germans.

“The end of slavery was near and there was the problem of where to find new workers. People knew that slavery could no longer be maintained in the long term and that it was becoming increasingly difficult to get supplies because of the British blockade of the slave trade. And that's when they turned their attention to the German territories. They knew that there were also many poor people there who were forced to emigrate.”

Stefan Rinke, historian at the Institute for Latin American Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin.

Brazil needed immigrants and wanted them to be from Central Europe. If the first two reasons were solely about the need to have people who would cultivate the country's lands and be ready to fight Brazil's enemies. The third motivation concerned the desire to “whiten” the Brazilian population.

“They wanted Europeans. And not all Europeans, but especially those from Central Europe, because they were considered to be particularly virtuous, hardworking, ambitious, and obedient, which is not unimportant if new subjects were wanted.”

Stefan Rinke

Over a century, Germans who found a home in Brazil grew from 280 to about 250,000. The fourth-largest nationality to immigrate to the country, after Portuguese, Italians and Spanish.

Several reasons led to the formation of this huge flow of immigrants. From the failure of the revolutions of 1848 to the transformation of European society due to industrialization, but also from the attractive force of a new world that was emerging across the ocean.

The settlement of the Germans, their growth and development, came at an enormous price. Those who paid it were the jungle-dwelling indigenous, who had to fight bloody battles against the Germans.

The government took the side of the newcomers, hiring mercenary troops who hunted down the indigenous, who were named Bugre. A discriminatory term.

Two-thirds of the indigenous population was wiped out.

“There is no street in São Leopoldo named after a black or indigenous person,” São Leopoldo journalist Dominga Menezes told the Guardian. Author of a book about how the focus on German migration silenced the stories of black and Indigenous people in the region.

The German community continued to thrive. People maintained their customs and expressed themselves using their idioms. Few spoke Portuguese, and Germans tried not to mix with Brazilians. The bond with the motherland remained strong, until the advent of National Socialism.

Brazil found itself in a rather uncomfortable situation. It had a large segment of the population internally that supported the policies of Adolf Hitler, plus there was the largest Nazi party outside Germany, and children sang Nazi hymns in schools. When German submarines sank Brazilian ships, Brazil declared war on Germany. Internally, the use of the German language was forbidden, the Nazi party was banned, and German clubs and schools were closed.

After the end of World War II, the “German” Brazilians broke away from the motherland. Communities began to mix with the Portuguese, and the use of the German language saw a very sharp decline, but it did not disappear, quite the contrary.

To this day, German is the second most spoken idiom in Brazil. There are an estimated 3 million, people who are still able to speak it today. The survival of the language has been made possible by compulsory teaching in schools in German immigrant communities.

In addition to the language, some traditions have survived unchanged. Such as the Oktoberfest in Blumenau, for example, or the half-timbered houses, but also typical dishes such as sauerkraut with pork knuckle or apple strudel.

Also, people's last names did not change. Unlike in the United States, where immigrants had both their first and last names changed upon arrival. Donald Trump's grandfather (born in Kallstadt, Germany) whose name was Friedrich Trumpf, upon his arrival in New York, was registered as Fred Trump.

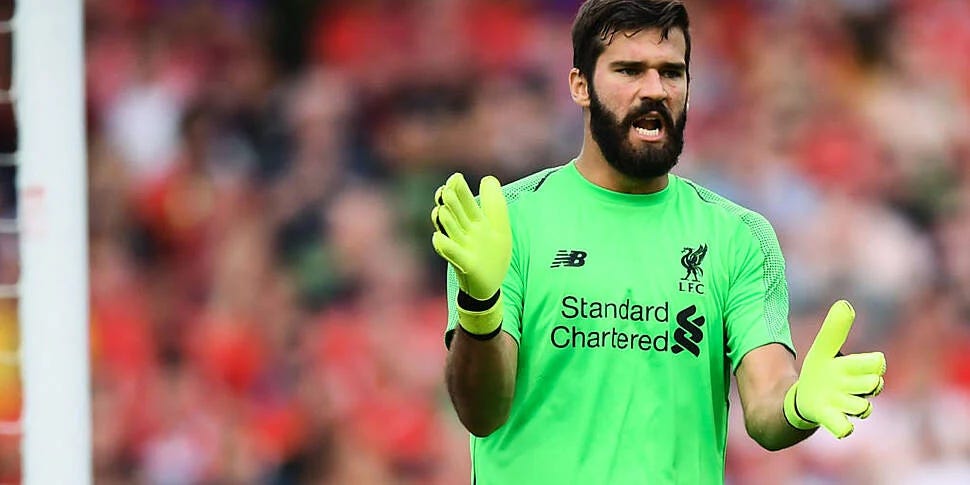

In Brazil, it is very easy to tell if a Brazilian has German ancestry. It is enough to read his last name. As in the case of Brazilian goalkeeper Allison Becker.

Alisson Becker

Alisson's personal story is interconnected with German migration to Brazil.

It was precisely his ancestors who were the first to migrate from the Saar to southern Brazil. They were among the founders of the city of Novo Hamburgo. Hometown of the Brazilian national team and Liverpool goalkeeper.

It was Nikolaus Becker who was the first to cross the ocean and settle in São Leopoldo, the centre of German immigrants. There, he started the first tannery in the region. Five years later, he married Angela Krämer, with whom he had ten children.

Today, Novo Hamburgo is a city of 240,000 inhabitants and is considered Brazil's footwear capital. It represents the centre of the leather and footwear industry.

And one of the streets is named after Nikolaus himself, “Avenida Nicolau Becker.” Jose Agostinho Alisson, the goalkeeper's father, spoke German and worked in the shoe industry until his death, which occurred in 2021.

At Roma, where Becker played for two seasons, he was renamed precisely as “the German.”

“Solid, rational, and cold.”

In addition to the nickname, Alisson tried to become a German citizen by applying for citizenship. He was not granted a German passport, because he represents the seventh generation of his family branch and German citizenship is given until the third generation.

A tiny revenge

The last major tournament match in which Germany and Brazil met was the final of the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016.

Unlike two years earlier, Neymar was also on the field. That night, no bad injury prevented him from playing.

It was he who put his team ahead with a spectacular free kick. The Germans equalized with Meyer, and the match ended in a 1-1 draw.

To decide the winner, penalty kicks were needed. The Germans missed the fifth, and the last to kick was Neymar himself.

The Brazilian star scored. He got emotional and his teammates ran to celebrate with him.

Winning a gold medal is not comparable to winning the World Cup, but it is still a revenge that Brazilian football needed.

A small plaster, to cover a wound that will be difficult to heal.

And if all of Brazil celebrated the victory that night; most likely, only in Santa Catarina there might have been somebody sad about the German defeat.

Sources:

https://www.amazon.de/Futebol-Nation-Footballing-History-Brazil/dp/0241969778

https://blog.rosettastone.com/what-languages-are-spoken-in-brazil/

https://www.babagol.net/blog/2016/08/20/the-germano-brazilian-connectionhtml

https://www.rivistaundici.com/2018/06/15/alisson-il-portiere-del-futuro/

https://www.dw.com/en/why-did-germans-immigrate-to-brazil-200-years-ago/a-69712593

https://www.ku.de/news/students-investigate-use-of-german-dialect-in-southern-brazil