1974 and All That

How Zaire’s Year of Sport Reflected its Troubled Past, Present and Future

1974.

Zaire found itself thrust onto the world stage in a way few could have predicted a couple of years earlier. Not only had the Central African nation qualified for its first-ever FIFA World Cup, but it hosted one of boxing history’s most iconic events - the Rumble in the Jungle.

Within a matter of months, Zaire became synonymous with sporting spectacle and a carefully choreographed narrative. Behind the country’s public profile though was a tumultuous history - a legacy of colonial exploitation, Cold War plots and domestic instability.

Before Zaire became a platform for sporting and political ambitions, it endured a darker history. Once known internationally as the ‘Congo Free State’ and later the ‘Belgian Congo,’ the nation suffered under the brutal regime of King Leopold II until he was forced to relinquish it to the colonial rule of the Belgian government.

Millions of people lived and died under a system that prioritised rubber processing and the collection of ivory over human life. During this period, the country’s population plummeted as the birth rate fell, smallpox spread and draconian killings were carried out.

Following independence in 1960, the country’s political landscape was volatile. Visionary leaders like Patrice Lumumba emerged, only to be undermined by scheming Cold War powers. The CIA were alleged to have colluded with Belgian authorities to destabilise Lumumba’s left-wing government and eventually assassinate him in January 1961.

This foreign interference paved the way for anti-communist politician Mobutu Sese Seko to be installed as an autocratic leader. The former general changed his country’s name to Zaire and set out on a campaign to erase all traces of colonialism, amassing a vast personal fortune in the process. But he was also hell-bent on using every available tool - including sport - to forge a new national identity.

Under Mobutu’s regime, sport became more than a game. It became an essential vehicle of national rejuvenation. His ‘authenticity campaign’ sought to project an image of modernity and self-reliance to the world. Investing heavily in sports was a key element of this strategy. Football, with its rapidly growing popularity across Africa, and boxing - symbolic of individual toughness - were seen as ideal canvasses to paint narratives of strength and progress.

Major sporting events were used to distract from the everyday hardships faced by Zaireans. By aligning international sporting successes with national pride, Mobutu aimed to rewrite the nation’s troubled history and present it as a beacon of African resurgence.

The early 1970s were a time of bold ambitions in Zaire. Football had emerged as the sport of the people, and the national team’s qualification for the 1974 World Cup was rightly celebrated as a monumental achievement. Zaire’s success in the African Cup of Nations had already positioned it as a rising force on the continent.

Beneath the surface, the players faced immense pressure to embody the political ideals of Mobutu. The build-up to the tournament was as much an exercise in propaganda as it was a sporting endeavour - with every training session and public appearance under the watchful eye of the authoritarian regime.

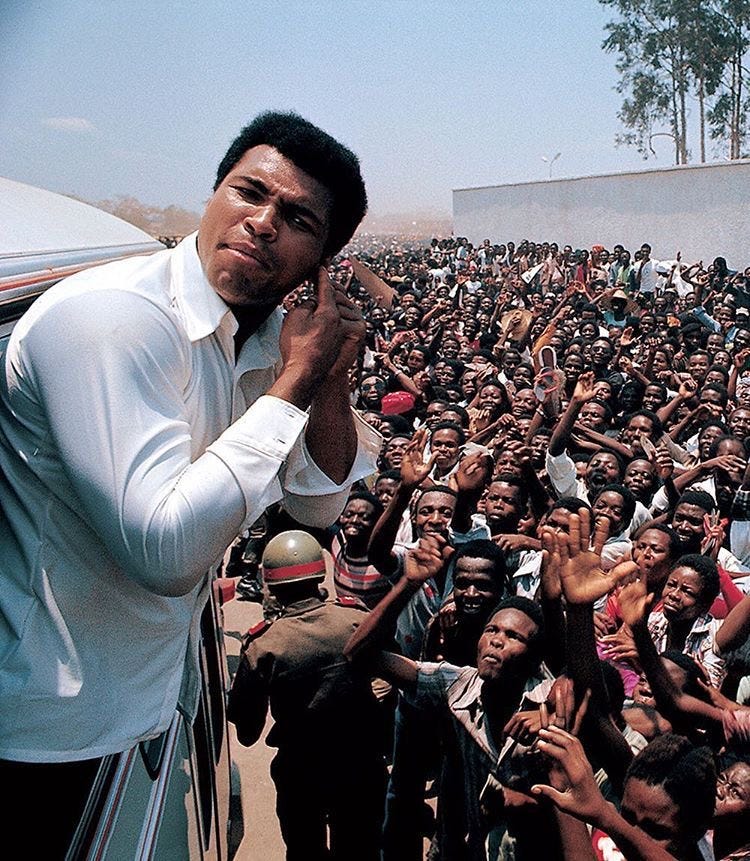

Meanwhile, Zaire was preparing to host another event that would captivate global audiences: the Rumble in the Jungle. This high-profile boxing match, pitting the legendary Muhammad Ali against the formidable George Foreman, was to become a defining moment in the nation’s history.

For Zaire and Africa, the national team’s qualification for the World Cup was a breakthrough. Before the tournament began, the national team were heralded as ambassadors for the continent. However, reality on the pitch was a far cry from the level of expectation.

Zaire’s World Cup campaign in West Germany was a quick combination of punishing blows. A somewhat respectable 2-0 loss to Scotland was quickly followed by a crushing 9-0 defeat to Yugoslavia.

The final group match against Brazil, which saw the infamous free kick incident involving Mwepu Ilunga, proved to be the knockout punch. To the outside world, these performances were not just footballing failures but symptoms of a deeper malaise. The nation was clearly burdened by the weight of political pressure.

As Zaire’s defenders formed a defensive wall, Ilunga sprinted forward and hoofed the ball downfield. The referee immediately booked him, while Brazilian players looked on in disbelief. To spectators, it seemed as though the Zairean didn’t know the rules of the game - an assumption that has since been debunked.

In reality, Ilunga’s behaviour reflected his frustration. By this point, the Zaire team were under immense pressure from Mobutu’s regime, having allegedly been threatened with severe punishment should they concede more goals. Some reports suggest they had also been financially punished, with their promised bonuses revoked after the 9-0 humiliation.

Mwepu Ilunga later explained that his actions were, in fact, a protest - a way to break the game’s rhythm and send a message that all was not well in the Zairean camp. What appeared to be a bizarre misunderstanding was defiance from a player feeling trapped in a dangerous situation.

Just months after the World Cup debacle, the Rumble in the Jungle offered something a little more exciting. In the heat of the capital, Kinshasa, the world first witnessed Muhammad Ali’s famous ‘rope-a-dope’ strategy against the seemingly flawless George Foreman.

Unlike the despair that defined the football team, Ali’s triumph was electrifying - a display of resilience and tactical prowess. His victory was celebrated, not only as a sporting triumph, but also as a symbolic reclamation of power by those who had suffered under post-colonial oppression.

The two spectacles encapsulated the paradox of 1974 in Zaire. The football team’s experience demonstrated the impact of a regime applying immense pressure - where every defeat was amplified by the threat of retribution from Mobutu’s government. Whereas the boxing match became a beacon of hope, when the individual defied overwhelming odds.

The fallout from these major events was swift. The national football team, once celebrated as the pride of Zaire, were simply cast aside. The disastrous World Cup campaign was met with public humiliation and political scapegoating. The Rumble in the Jungle however, left an indelible mark on the sporting world.

Zaire’s use of sport as an instrument of the state in 1974 set a precedent - a tactic not confined to Mobutu’s government. But it did demonstrate how sports like football and boxing could be leveraged to mask internal dysfunction and distract from issues like decades of human rights abuses and Cold War tensions.

The echoes of this strategy were evident in many regimes that followed, from the Soviet Union to Argentina, where sporting success was used as a proxy for political legitimacy.

The shift from Zaire to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was not merely a name change. It was representative of a struggle for genuine national reinvention. Despite the events of 1974, the legacies of colonial trauma, corrupt governance and foreign interference continued to haunt the people of this country.

Today, the DRC is mired in conflict. Ethnic tensions have resurfaced and the struggle for control over the region’s abundant mineral wealth is ongoing. In truth, the failures and triumphs of 1974 are not relics of the Cold War era but continue to influence the challenges faced by the DRC today.

In the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, in which Hutu extremists slaughtered an estimated 800,000 Tutsi people, millions of refugees fled to Zaire. Among them were remnants of the Hutu extremist militias, who used refugee camps as bases to launch attacks into Rwanda. This prompted the Rwandan and Ugandan governments to support a rebellion against Mobutu, culminating in the First Congo War in the late 1990s and the autocrat’s eventual overthrow.

Rather than stabilising the region, Mobutu’s downfall plunged the DRC into deeper despair. The Second Congo War, which continued into the new millennium, dragged more African nations into the fray and further entrenched ethnic divisions. To this day, paramilitaries continue to exploit ethnic allegiances and compete for control over natural resources.

Ultimately, 1974 was not just about competition played out on a field or in the ring; it was about a nation craving a fresh start and an authentic source of national pride. As we reflect on that turbulent year, and what has unfolded since, we’re reminded that the intersection of sport and geopolitics is never straightforward.

Sam writes the newsletter Maldini’s Chain, which covers insights and stories from the world of international football, including its culture and history. https://maldinischain.substack.com/